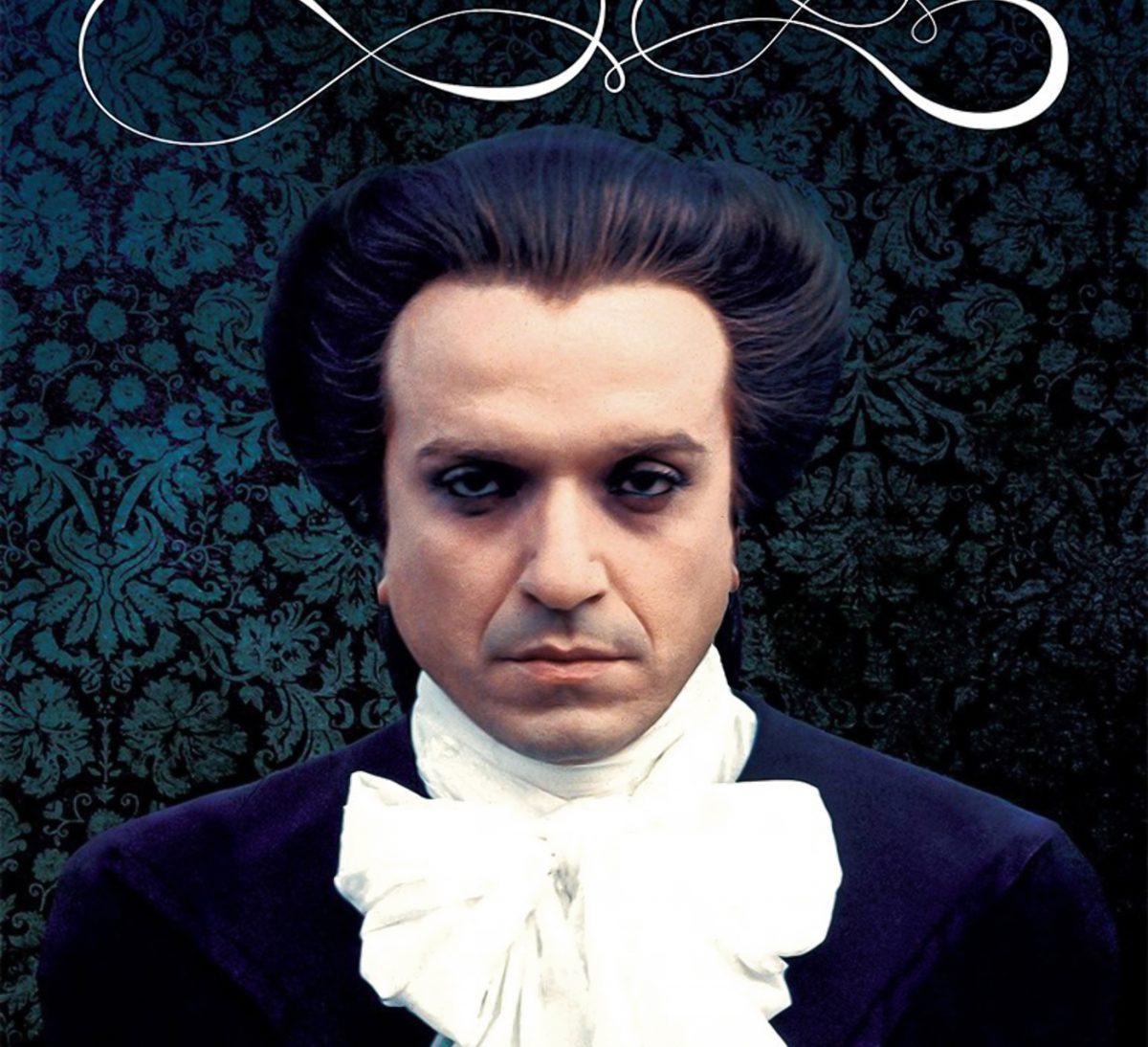

Don Giovanni

Joseph Losey

France – 1979

Screenplay: Lorenzo da Ponte, Frantz Salieri, Patricia Losey, Joseph Losey

Cinematography: Gerry Fisher

Production: Gaumont, Caméra One, Opera Film Produzione, France 2, Janus Film und Fernsehen, Opéra National de Paris

Language: Italian

Duration: 185 min

Color: Color

Synopsis: Don Giovanni is a womanizing libertine who conquers the hearts of women throughout Spain. Accompanied by his manservant Leporello, he sneaks into Il Commendatore’s house with the intent to seduce his daughter Donna Anna. The young woman screams and wakes up the old nobleman, who challenges the intruder to a duel. Il Commendatore is killed a devastated Donna Anna vows avenge his murder. Giovanni continues to seduce and toy with women, including a former lover who is determined to see him suffer for his betrayal, and a peasant girl, Zerlina, whom he ravishes on the eve of her wedding. When they all band together to bring Don Giovanni to justice, he persuades Leporello to trade clothes, and the faithful servant barely escapes with his life. As Don Giovanni gloats over his own cleverness and gets progressively drunk, he suddenly hears Il Commendatore’s voice from beyond the grave and, mockingly, invites the ghost to dinner. Sitting at an extravagantly laid out table, Don Giovanny hears ominous knocks at the door. Leporello is cowers in fright, but devil-may-care Giovanni opens the door to find the statue of Il Commendatore. Giovanni refuses him entry, but Il Commendatore demands that the sinful Don repent for his transgressions.

Notes: Losey never fit easily within the auteur paradigm. He was not a writer-director, and three of his most remarkable films were made in close collaboration with Harold Pinter, the influential stage dramatist whose stature eclipsed that of Losey’s. As a result of this, Losey was ostracised by some of the same auteur critics who championed his early Hollywood and British genre films like the film noirs The Prowler (1951), Time Without Pity (1957), and The Criminal (1960), as well as the science fiction-cum-juvenile delinquent film The Damned (1963, filmed in 1961). This backlash was in large part due to the fact that after he directed Eve (1962, a French-Italian sexual melodrama with Jeanne Moreau, which, like The Damned, was heavily recut by its producers) and The Servant, he began distancing himself from genre films (the type of films typically exalted by auteur critics) and instead became increasingly associated with literary adaptations and art-house cinema (the type of films they often criticized). “With Accident, Losey has escaped the clutches of the cultists to fall into the hands of the snobs,” Sarris declared in 1968.

Losey was a stranger to his fellow filmmakers on both sides of the Atlantic. Whereas many of his Hollywood contemporaries shunned hum for being blacklisted, his British colleagues gave him only faint praise. He was viewed as a cynical foreigner who became increasingly pretentious in his storytelling. His American identity – and particularly, his past as a Hollywood director – worked against him, since many critics refused to unequivocally accept Hollywood filmmakers as artists. When Losey went from making film noirs to art-house like Accident and Don Giovanni (1979), an exuberant adaptation of Mozart’s opera, the transition was probably interpreted by some as the result of his collaboration with Pinter. In the 1970s, Losey and Pinter began envisioning an elaborate and very expensive adaptation of Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu, but the project never took off and Losey was no longer considered bankable. The poor reception of films from that era – The Assassination of Trotsky (1972), A Doll’s House (1973), Galileo (1975), The Romantic Englishwoman (1975), and Don Giovanni – sealed his reputation as a director who tended to alienate audiences with his high art subject matter and narrative style.

Losey’s career was marked by adversity and perseverance amidst a post-war filmmaking landscape that perceived him as both a political subversive and an industrial outsider. He mirrored his blacklisted contemporaries Jules Dassin and Cy Endfield by resurrecting his career in Europe, where he compiled an admittedly uneven, yet intermittently brilliant, filmography. Losey’s films challenged both ideological and stylistic sensibilities. Renouncing films offering easy solutions, Losey came to feel that films “can only provide a stimulation which I think at its best is some sort of complete artistic statement, which therefore is form and emotion, which will stimulate the people seeing, hearing, absorbing it, to further thought and investigation.” In an era when many of his past Hollywood contemporaries like Elia Kazan, Nicholas Ray, Orson Welles, and Fred Zinnemann were either concluding their filmmaking careers or experiencing difficulties securing funding, Losey remained prolific and made a film almost annually until his death. If anything, his vision to bridge the gap between commerce and high art was, and to a large extent still is, before its time.

Notes drawn from Leonard, Suzanne, and Yvonne Tasker. 2014. Fifty Hollywood Directors. Routledge.