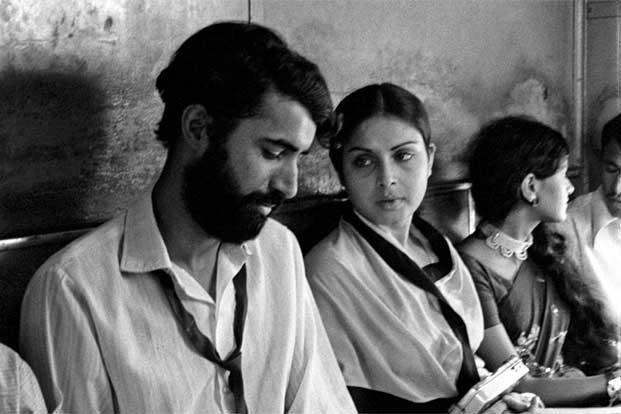

27 Down

Awtar Krishna Kaul

India – 1974

Screenplay: Awtar Krishna Kaul

Cinematography: Apurba Kishore Bir

Production: National Film Development Corporation of India (NFDC)

Language: Hindi

Duration: 115 min

Color: Black and White

Synopsis: On 27 Down, the Bombay-Varanasi Express line, an older Sanjay is on a pilgrimage journey. He recalls episodes from his life as familiar landscapes emerge along the way. As a young boy, his father, Anna, had been severely crippled by a work-related accident at the railway. Having grown old enough to work, Sanjay gives up his dream of becoming an artist in order to support his family and, with Anna’s help, takes up a job as a ticket checker. He meets a Life Insurance Corporation employee, Shalini, on the suburban train, and after a few encounters they fall in love. Sanjay begins to see life in new ways, but when his traditionalist father finds out about the relationship, he quickly arranges a marriage with a girl from the village. Sanjay accepts the match, reluctantly, but is unable to get Shalini out of his mind and heart.

Notes:

27 Down was Awtar Kaul’s only film and won the Award for Best Feature Film in Hindi as well as Best Cinematography for Apurba Kishore Bir at the 21st National Film Awards in 1974 (the director died in an accident the same week the awards were announced). The film was shot on location on Mumbai trains, platforms, and at Mumbai’s Victoria Terminus station. A majority of the scenes was shot using a hand-held camera in a style inspired by The Battle of Algiers (1966), with an aim to put the camera right in the middle of the action.

If the Indian New Wave is characterized by cinematic experimentation and new forms of film narration recognized in the avant-garde work of Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani, another characteristic of the movement is cinematic realism, both in form and content, evident in a number of films: Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome, Basu Chatterji’s Sara Akash, Kantilal Rathod’s Kanku, all from 1969, Pattabhi Rama Reddy’s Samskara (1970), Rajendra Singh Bedi’s Dastak (1970), M.S. Sathyu’s Garm Hawa (1973) and Awtar Kaul’s 27 Down (1973), among many others. The ‘new Indian cinema’ that these films inaugurated was clearly connected to a concern with aesthetics, to a seriousness of intent, and to a representation of social issues with a drive towards an understanding of reality in all its complexities, contradictions and ambiguities, necessary, it was believed, for the transformation of society. A missionary zeal was this obvious in the work of a lot of the Indian New Wave directors who focused on the ills of Indian society: poverty; social injustice; the inherent violence of social structures evidenced in the modalities of entrenched feudal power; the oppressive stranglehold of the orthodoxies of tradition; and the brutal subjugation and exploitation of lower castes and of women. As a critical movement with a ‘social conscience’, the New Wave believed that it had a political role to play at a crucial juncture of national history.

What is remarkable about this moment of cinematic history is the tremendous diversity of forms that this new cinema generated. Launched by the investment made by the Film Finance Corporation (FFC) – later known as the National Film Development Corporation of India (NFDC) – the movement burgeoned into what came to be seen as a wave of offbeat, artistic cinema. At the same time, it was not as if the films shared political or aesthetic ideologies or positions, marked as they were by an immense variety of concerns and styles. Yet, there were common responses and larger approaches that were evident in the work that was financed by the FFC and a few others during this period, which can be seen as constituting an aesthetic and cultural movement. These were a rejection of the values, forms, performance modes and the style of mainstream, commercial cinema that privileged entertainment values, spectacular display and melodrama; a vision of cinema as an expressive art form; an inspiration from a sense of connectedness to a larger and ‘serious international artistic enterprise’; and what can be termed in a general sense, a realist project – one that is motivated by the drive to know and represent the world adequately. At the same time, a realist project in this larger sense is not to be equated only with cinematic realism, for the project of addressing reality in its broadest sense did inspire carried aesthetic forms demonstrating that the impulse to engage reality could undergird different aesthetic expressions from cinematic realism to modernism. The New Wave films were extremely diverse, and ranged from realist portrayals of contemporary Indian reality, especially the reality of small town and village India to experimental and modernist work that foregrounded abstraction and stylization.

Excerpt from Gokulsing, K. Moti, and Wimal Dissanayake. 2013. Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas. Routledge. – additional notes by Theo Stojanov.