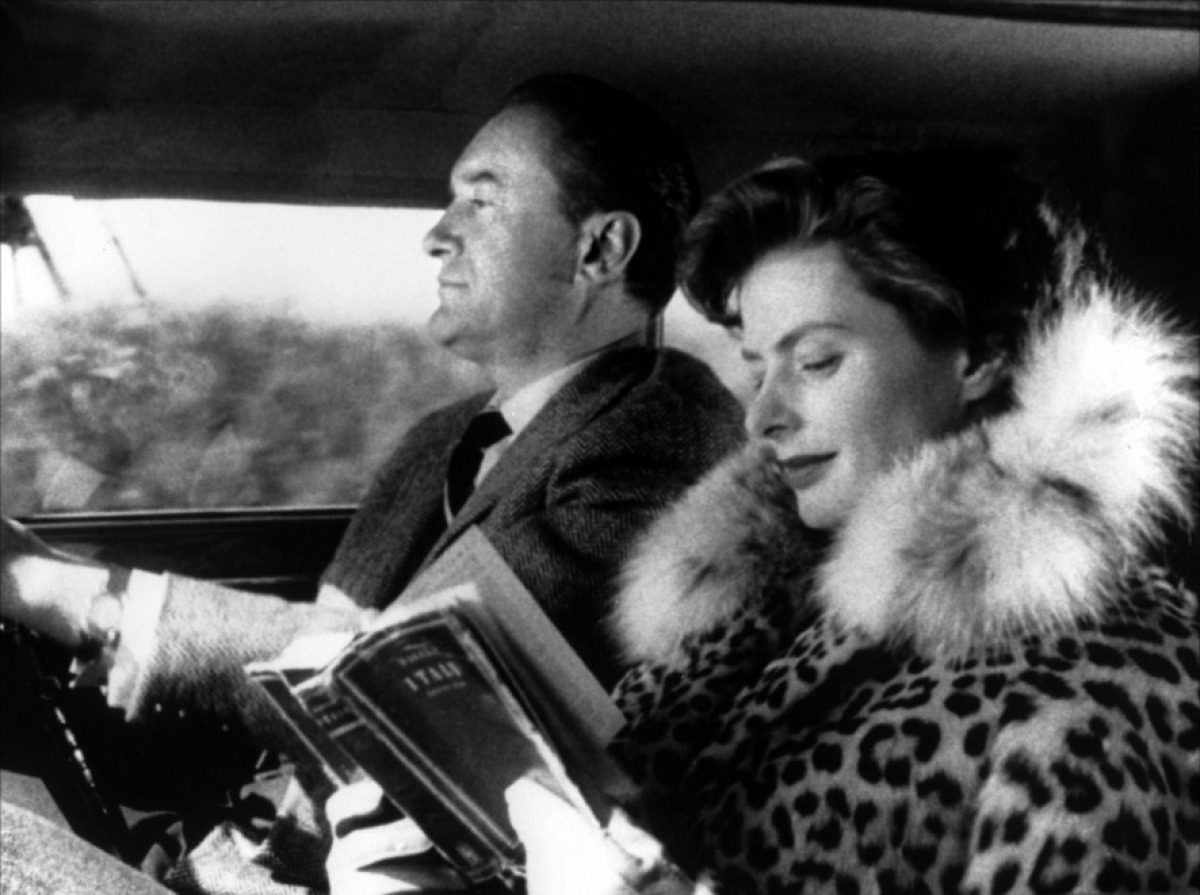

Journey To Italy

Viaggio in Italia

Roberto Rossellini

Italy – 1954

Screenplay: Vitaliano Brancati, Roberto Rossellini, Antonio Pietrangeli

Cinematography: Enzo Serafin

Production: Italia Film, Junior Film, Sveva Film, Les Films Ariane, Francinex, Société Générale de Cinématographie

Language: English, Italian

Duration: 97 min

Color: Black and White

Synopsis: Catherine and Alexander, wealthy and sophisticated, drive to Naples to dispose of a deceased uncle’s villa. There’s a coolness in their relationship and aspects of Naples add to the strain. She remembers a poet who loved her and died in the war; although she didn’t love him back, the memory underscores the absence of romance in her life now. She tours the museums of Naples and Pompeii, immersing herself in the Neapolitan fascination with the dead, while at the same time observing the many pregnant women around; he idles on Capri, flirting with women but drawing back from adultery. With her, he’s sarcastic; with him, she’s critical. They talk of divorce. Will this foreign couple find insight and direction in Italy?

Notes:

George Sanders and Ingrid Bergman are both quite good in Journey to Italy, despite their unfamiliarity with Rossellini’s method of filmmaking. Their Hollywood professionalism was tested by the unique way in which Rossellini not only directed, but the way he fashioned the characters and the narrative. Sanders was used to productions that were “script-based and character orientated,” in Laura Mulvey’s words, and as she notes, Rossellini was growing impatient with storytelling. Neither Sanders nor Bergman were accustomed to working with amateurs, which was part and parcel for Rossellini’s continued commitment to reality. As such, the star personas and personalities were, at times, visibly in conflict with the performances. Just as this difference in methodology ultimately and inevitably informs the film’s form, so did the similarly untidy lives of both actors and the director. In an autobiographical vein not unlike so many filmmakers to come, Rossellini utilizes real relationships in turmoil (Rossellini and Bergman – a couple at the time – were on the rocks, and Sanders was in the midst of separating from Zsa Zsa Gábor), to give Journey to Italy some realistic credence when it comes to the ups and downs of various affairs.

Compared to Rossellini’s neorealist features, there is a distance here and comparatively little to empathize with. Stylistically, Journey to Italy is different from Rossellini’s preceding two films as well, in that it does not have the harshness of Stromboli or, on the other side of the spectrum, the refined lighting of Europa ’51. Italian neorealism had largely ignored psychological realism, focusing instead on the effect of the environment on characters. This film helped to move Italian cinema back toward a cinema of psychological introspection and visual symbolism where character and environment served to emphasize the newly established protagonist of modernist cinema, the isolated and alienated individual. With Journey to Italy, Rossellini was pushing the boundaries of cinematic storytelling further and further, changing the way in which stories were presented and continually challenging the audience’s reception to, and understanding of, those narratives. Ambiguous causal factors thwart traditional character identification, and formal devices at once convey an unadorned authenticity and stand out in terms of their calculated construction. Certainly, this film was not of the mainstream in its depiction of a new reality; it attempted to express new concerns through new methods, setting the foundation of a new new realism.

Excerpt adapted from Carr, Jeremy. “Journey to Italy: A New, New Realism.” Film International (16516826) 12, no. 3 (September 2014): 137-141.