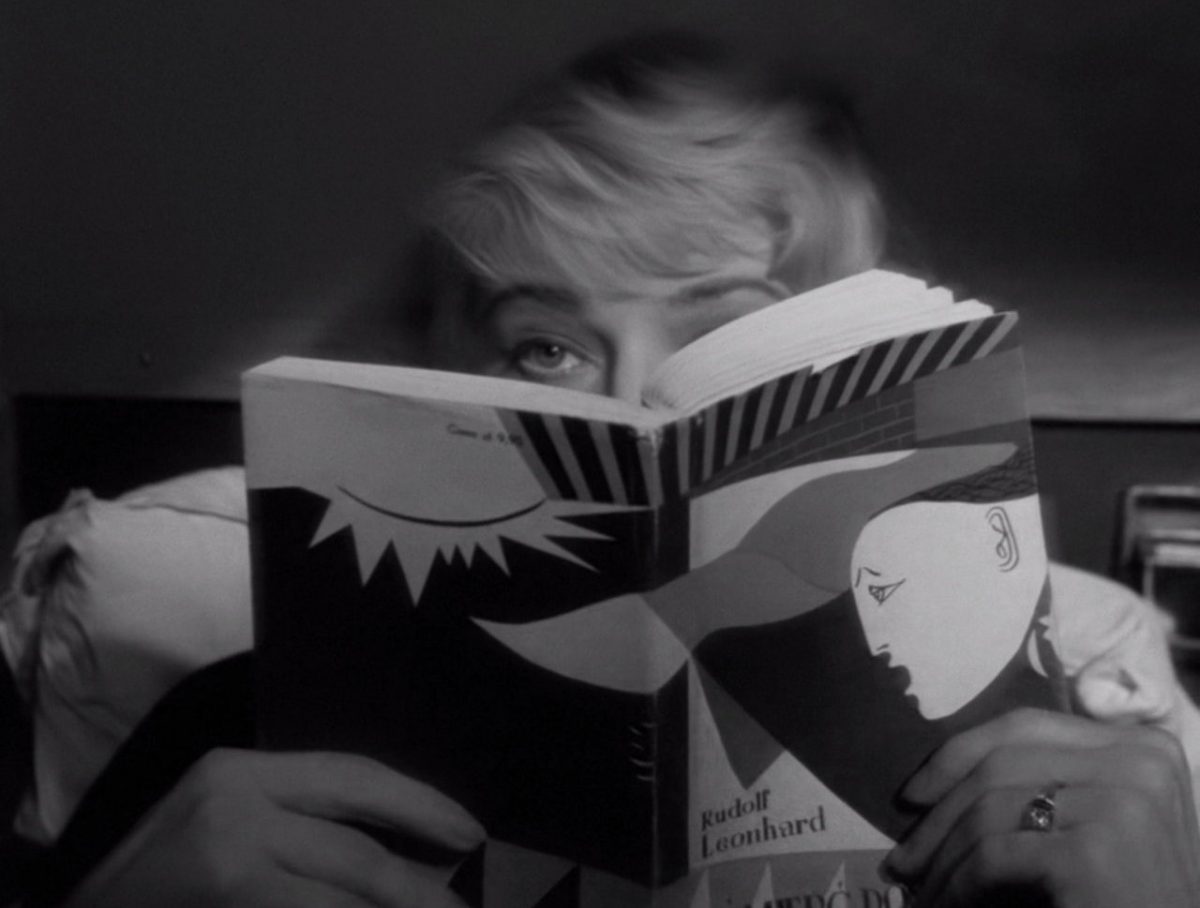

Night Train

Pociag

Jerzy Kawalerowicz

Poland – 1959

Screenplay: Jerzy Lutowski, Jerzy Kawalerowicz

Cinematography: Jan Laskowski

Production: Zespól Filmowy “Kadr”

Language: Polish

Duration: 99 min

Color: Black and White

Synopsis: Two strangers, Jerzy and Marta, accidentally end up holding tickets for the same sleeping compartment on an overnight train to the Baltic Sea coast. Also on board is Marta’s spurned lover, who will not leave her alone. When the police board the train in search of a murderer on the loose, rumors abound and everything seems to point toward one of the main characters as the culprit.

Notes:

Although this most cosmopolitan of Polish directors began about the same time as compatriots Wajda and Munk, the major works of Jerzy Kawalerowicz do not belong to the “Polish school.” As a rule, he’s more interested in the fate of individuals than the fate of the nation. Attracted by existential problems, Kawalerowicz has never been faithful to one genre; what some of his films do have in common is his preoccupation with the extent to which fanaticism, whether political or religious, can influence events. He stages drama in long takes, translating inner turmoil into austere images reminiscent of Dreyer. His masterpiece is considered to be Mother Joan of the Angels (1961), and his most recent film, an adaptation of Quo Vadis (2001). Kawalerowicz came into his own with Night Train (1959), which is marked by the post-Stalin cultural thaw in mid-1950s Poland. The film is a claustrophobic suspenser that recalls Hitchcock on numerous levels, not least an initial mix-up that sees two opposite-sex strangers sharing a sleeper compartment. Both Marta and Jerzy harbour secrets: visible scars on her wrists suggest past trauma, while he reacts violently to an accidental bedsheet arrangement that recalls a shrouded corpse in a morgue. There’s a murder, but it’s happened already, and Kawalerowicz is far more interested in the psychological fallout not only on this odd couple but also their diverse travelling companions, who include Marta’s foppish former lover. The eerie, echoing vocals hummed by a female voice on the jazz soundtrack by Andrzej Trzaskowski add to the disorienting effect. Refreshingly free of Hollywood clichés, this film draws on Expressionist influences in the artfully planned staging and unusual camera angles, both inside the cramped railway corridors and outside the train in various stops along the way. The film is fairly demanding on the viewer: there are a lot of secondary characters with complicated stories of their own. All of Kawalerowicz’s films deal with individual fate in a society being crushed by overwhelming external forces, whether war or politics, in an attempt to examine moral choice under pressure. Night Train is no exception, only here he has created an allegory of misfits among a society of passengers, a society that is predictable, suspicious of individuality, and eager to punish.

Excerpt from Stein, Elliott. “History Lessons: The Films of Jerzy Kawalerowicz.” Village Voice, January 28, 2004., with additional notes by Theo Stojanov.