Purple Noon

Plein soleil

René Clément

France / Italy – 1960

Screenplay: René Clément, Paul Gégauff

Cinematography: Henri Decaë

Production: Robert et Raymond Hakim Paris Film Paritalia Titanus

Language: French, Italian, English

Duration: 115 min

Color: Color

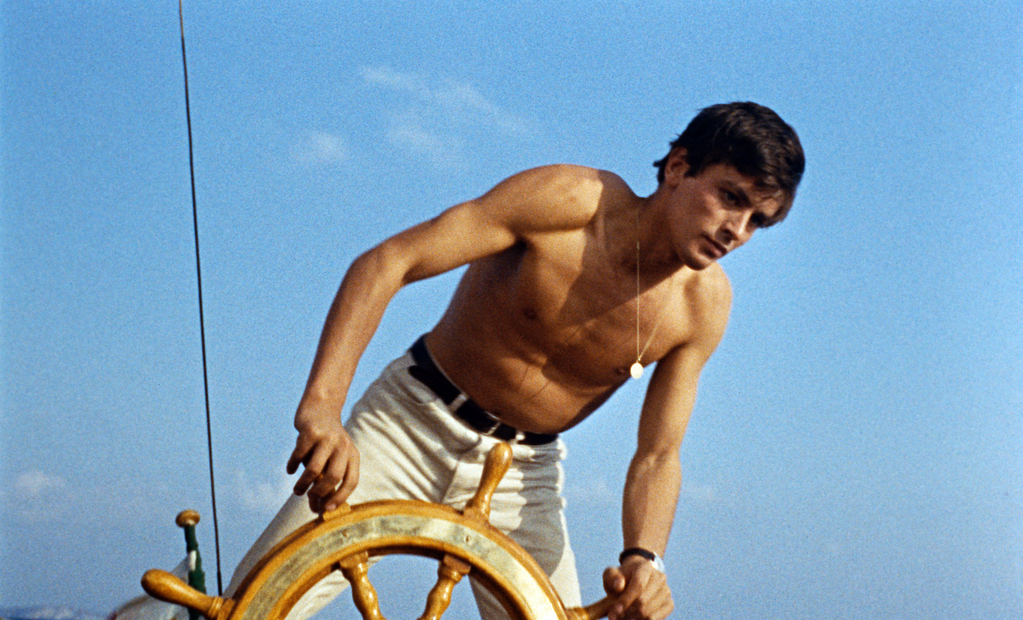

Synopsis: Tom Ripley is a young man struggling to make a living by whatever means necessary. He is approached by shipping magnate Herbert Greenleaf to travel to Italy and persuade his idle son, Philippe, to return to the United States and join the family business. Ripley agrees, exaggerating his friendship with Philippe, a half-remembered acquaintance, in order to gain the elder Greenleaf’s trust. In Rome, Philippe finds Tom amusing, but has no intentions of going anywhere. Marge, Philippe’s fiancée, feels sorry for Tom but resents his lingering presence, and their rich young friends generally consider Ripley to be a worthless moocher. After a while, Mr. Greenleaf considers the mission a failure and frees Tom from all obligations, just as Philippe is beginning to get bored with his disposable friend. Desperate to retain the carefree lifestyle he has briefly tasted, Tom kills Philippe, and assumes his identity. However, he will need all of his conman abilities to keep Philippe’s friends and the police off the trail.

Notes:

René Clément’s Plein Soleil (Purple Noon) is a vivid adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” adapted once more, nearly forty years later, by Anthony Minghella. In Clément’s film the febrile beauty of Alain Delon reaches its height in his embodiment of the amoral Tom Ripley, in a fascinating, albeit peculiarly Gallic, revision of Highsmith’s novel. Unlike Minghella’s film, Purple Noon makes no excuses for Tom’s criminality. Clément is careful not to take pleasure in Tom’s plotting and maneuvering after he goes on the lam. It is no fun watching him replicate Philippe’s signature or drain his bank accounts. Instead, he is dogged by images of Catholic guilt. As he fumbles with the body of his latest victim, two priests pass by to remind him of his wickedness, while studious Marge is seen working on a manuscript on Fra Angelico.

There is a level of abjection in the book version of Ripley (and in Minghella’s adaptation) that allows him to resituate himself endlessly in pursuit of his desire, slipping between gender identities because his desire is not a person but an ideal: a becoming. That ambiguity is a huge part of Highsmith’s brilliance, but the script by Clément and Paul Gégauff eschews the character’s abjection and its related sexual ambiguity for Delon’s untroubled masculinity. Although some people see Ripley’s fascination with Philippe/Dickie Greenleaf as a kind of oblique sexual attraction, the truth is much more complex. The key moment of desire for Ripley is not tied to any person. What he lusts for is a state of being. People only represent ideals or obstacles. The only moment of ecstasy experienced by Ripley comes after the murder of Philippe/Dickie, when he takes up the trappings of Greenleaf’s world.

Clément started out making documentaries and made his first feature La Bataille du rail (1946) as a tribute to the part played by French railroad workers in the Resistance, shot on location and performed mainly by non-professionals (many of them the actual railroad workers involved). Awarded the Grand Prix at Cannes, it was widely hailed as heralding a French neorealist movement that never transpired. Although he was not directly associated with the nouvelle vague – especially after François Truffaut’s vehemently critical Cahiers essay “A Certain Tendency of French Cinema” – he often worked with a cinematographer who was, Henri Decaë. Decaë was Clément’s DP on Plein soleil. Following a series of films that enjoyed mixed reception, Clément made one more critically acclaimed feature, La Course du lièvre à travers les champs (And Hope to Die, 1972) which was drawn – as was Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player – from a crime novel by David Goodis; and like Truffaut’s movie, it’s a disorienting mix of thriller and fantasy. But for his refusal to adopt the particular aesthetics and ideology of the day, René Clément might indeed have been numbered among the nouvelle vague filmmakers. After a strong start in the 1940s and 1950s, his career waned into a morass of indifferent international co-productions, with the notable exception of La Course du lièvre à travers les champs.

Notes based on Laity, K. A. “Frenching Mr. Ripley.” Clues: A Journal Of Detection (Mcfarland & Company) 33, no. 2 (Fall 2014 2015): 67. and Tonguette, Peter. “Purple Noon.” Sight & Sound 23, no. 2 (February 2013): 117-119.