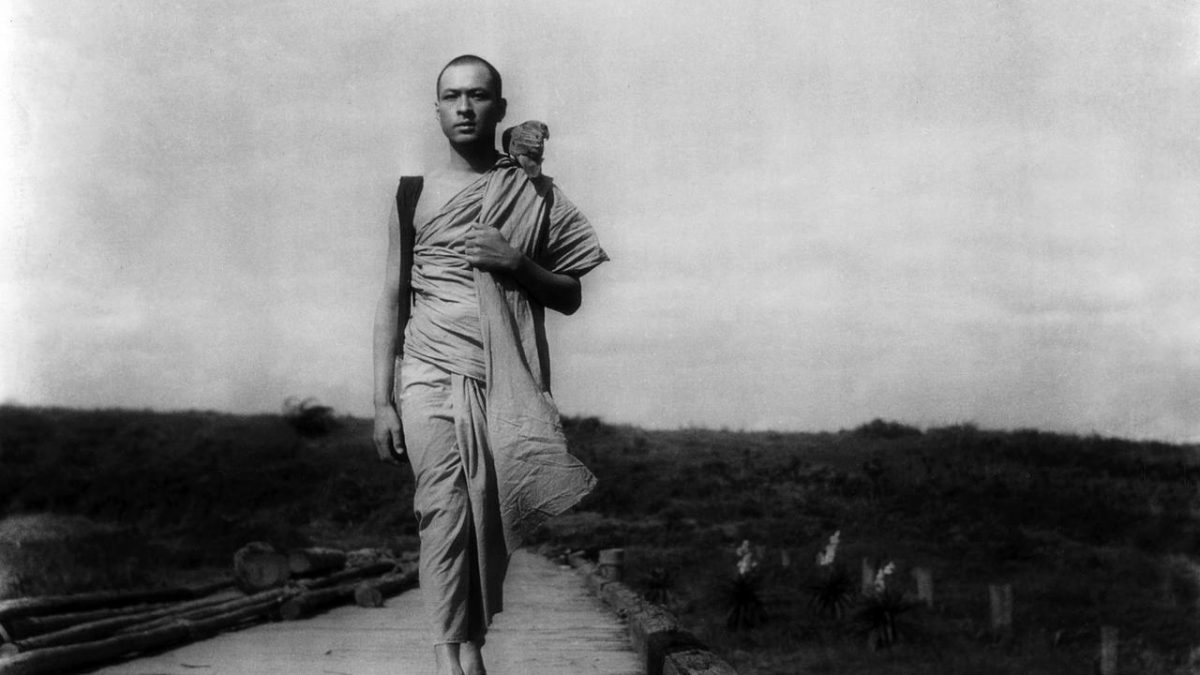

The Burmese Harp

Biruma no tategoto

Kon Ichikawa

Japan – 1956

Screenplay: Natto Wada

Cinematography: Minoru Yokoyama

Production: Nikkatsu

Language: Japanese, English

Duration: 133 min

Color: Black and White

Synopsis: In July, 1943, the Japanese army is on the retreat. Posted in Burma, Mizushima tries to keep up the spirits of his fellow soldiers with the sounds of his harp. The British ask him to go into the mountains and talk a Japanese platoon into surrender. With only 30 minutes to do it, Mizushima us unable to convince his fellow countrymen to avoid needless bloodshed for the sake of indifferent political powers, and is devastated when they choose to fight and die with honour. Deeply affected by a senseless war, he becomes a Buddhist monk and travels the countryside, burying the remains of those Japanese who never made it home alive. While his friends await repatriation, temporarily interned at the Mudon POW camp, Mizushima vows to remain in Burma, dedicating his life to prayer and the way of Lord Buddha.

Notes:

Ichikawa Kon’s The Burmese Harp (1956) and Fires on the Plain (1959) are films about the Japanese involvement in Southeast Asia during WWII, touching on issues that would not be addressed again until several decades later, in Eastwood Clint’s Letters from Iwo Jima (2006). The literary original of The Burmese Harp was written by Takeyama Michio in 1946, when the shock of surrender needed to be absorbed by the Japanese public. Ichikawa’s films undoubtedly carry a monumental antiwar message, but they also signal the vagaries of ideological contradiction surrounding the history of the Pacific War. He was a versatile filmmaker with a remarkably wide range of tones and styles that he employed throughout his career (seventy-seven films from 1945 to 2001, ranging from literary classics to documentary). Although he was not as demonstrably political as some of the New Wave filmmakers, Ichikawa had a strong sense of irony that gives his best films a subversive edge.

The central conceit of the film is that music can bridge cultural difference and create bonds between warring groups. The film’s theme song, intoned repeatedly by the singing soldiers, is a Japanese version of the British/American folk song “Home! Sweet Home!” which by the 1950s had become adapted as the popular Japanese song “Hanyo no yado.” The rousing choral collaboration between Japanese, American, and British troops, therefore, was an appeal for the cultural unification of Japan with its former allied enemies in Southeast Asia, though, as Canadian film scholar Catherine Russel observes, the film—shot almost exclusively in Japan—does not truly succeed in incorporating Burmese culture. Although this is certainly true, the international public recognized the film for another reason: it was a cultural attempt to reconcile differences and ask for atonement. Although Ichikawa had made twenty-six features prior to The Burmese Harp, this was the first film to bring the forty-one-year-old director national and international recognition when it won the prestigious San Giorgio Peace Prize at Venice.

Notes based on Russell, Catherine. “The Burmese Harp; Fires on the Plain.” Cineaste 32, no. 4 (Fall2007 2007): 63-64.